Out with the old…

Fiji’s Political Parties Decree [pdf] provided existing parties just 28 days to meet a number of tough requirements for their re-registration. Of the 16 parties that existed prior to the decree, only two, the National Federation Party (NFP) and the Fiji Labour Party (FLP), managed to meet the February 14 deadline and submit their applications.

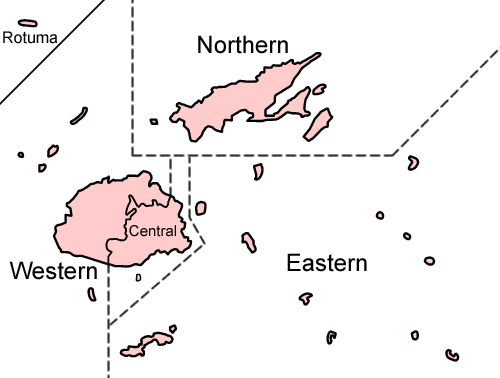

While much of the 19-page decree outlines a pragmatic framework, certain aspects have received significant criticism. Apart from the short time frame allowed for existing parties to re-register, common concerns relate to section 6 of the decree, whereby political parties are required to secure the names, addresses and voter card registration numbers of 5000 supporting members (up from 180 members in the past). Of those 5000, minimum numbers are also required to register from Fiji’s four main administrative divisions:

(i) Central Division – 2000 members

(ii) Western Division – 1750 members

(iii) Northern Division – 1000 members

(iv) Eastern Division – 250 members

Some political parties feel that membership requirements are too severe, but Fijian Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum disagrees. He has argued that since more than 500,000 people have registered to vote, it is perfectly reasonable for a political party to find less than 1% of those people to be party members. (Australia, with a population more than 20 times Fiji’s, requires only 500 members to form a political party.) Apart from securing 5000 members, parties are also required to establish offices in each of the four main administrative areas, and fulfill a multitude of other administrative requirements. Existing parties had to achieve all this within just 28 days.

The decree also gained condemnation from unions and earned a rebuke from the Australian foreign minister over restrictions on the involvement of union officials and public officers in political parties. Fiji’s notoriously feisty blogs are painting the decree as nothing more than a manifestation of Commodore Bainimarama’s long-term strategy to maintain power and to punish his most vocal critics by wrapping up parties of the past, weakening unions, sidelining Qarase and making life difficult for Chaudhry.

However, some of these onerous obligations might end up proving to be beneficial. By making registration more difficult and requiring parties to keep transparent accounting histories and proper administration systems in place, Fiji’s interim government is strengthening any political parties that do survive. Arguably, this will improve the accountability and quality of the political system overall. The decree also seems to be having a uniting effect among minor parties, forcing some ‘big men’ into alliances where before they stood alone. This may actually increase the opposition’s power and improve their chances in 2014.

Across Melanesia, there is a trend of democratic parties fracturing and forming more and more minor parties, arguably resulting in the degradation of the entire democratic process. Politics becomes encapsulated by constant battling between growing numbers of the ‘big men’. Take Vanuatu, a country with a population about a quarter the size of Fiji’s: in last year’s elections, no less than 34 different parties and 63 independents, constituting a total of 346 candidates, battled it out. In the end, prime minister elect Sato Kilman formed a patchwork coalition government with a cabinet composed of 9 different parties and one independent. Managing a coalition of so many competing interests doesn’t make the already difficult job of governing any easier.

With the bar raised so high, it is likely that only the strongest, most organised and best run political parties survive the transition. The decree could well be helping to cultivate a more successful political landscape down the track. Of course, this is not a foregone conclusion. There is the valid question of whether the bar has been set too high. While its probably no good to allow just any rag tag group to be able to form a political party, neither do you want significant minorities being completely excluded from the political process. In this case, only time will tell.

In with the new (?)

The 28-day rule applied only to existing political parties. New parties have until the elections in 2014 to register. This means that disbanded parties may not necessarily completely disappear. Once they have surrendered all assets to the state (as required by the decree) parties can draw upon their networks to combine or restart another party alone, albeit with a new name and look. One interesting case is that of the Soqosoqo Duavata ni Lewenivanua party (SDL) who allowed the 28 days to pass but with a plan to simultaneously start a new party, the Social Democratic and Liberal party –which, not coincidentally, just happened to have the same acronym. SDL, perhaps rashly, shared their plans, but on February 19th, with back up from the political party registrar, Ms Vuniwaqa, an amendment [pdf] to the original decree was released: no political parties would be allowed to have acronyms or symbols that had been used by former parties.

Further amendments restricting media coverage were also promulgated. Perversely, media organisations may no longer describe former political parties as “political parties” and may not report on any prospective political party either. Failure to comply will leave directors, editors, publishers and/or CEO of media organisations liable to receive fines of up to $50,000 or five years imprisonment or both. These are not empty threats -The Fiji Times being recently fined FJ$300,000 for publishing a story which included statements by the Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) general secretary, Tai Nicholas questioning the independence of Fiji’s judiciary.

Many have been quick to write off the decree entirely, but it’s worth considering what benefits may be derived and what implications the decree will have for Commodore Bainimarama himself, should he end up running for election as many predict. One might have assumed that as a politician, he might have preferred to face a shambolic multitude of minor parties that would prove easier to divide and conquer, allowing him to maintain his grip on the country. This decree though, likely ensures that the interim prime minister will be confronted by a larger, more cohesive opposition –and isn’t that what many have wanted all along?

It is easy to be critical of Voreqe Bainarama’s interim government and its unorthodox methods of moving towards democracy, but it does appear to be moving that way nonetheless. Provided the schedule doesn’t slip, Fiji is a mere 18 months away from a one man, one vote system, freer of racial disparities than at any time in the past. So while it is important, even necessary, to be good friends to Fiji and to respectfully share our concerns, there doesn’t appear to be much else the rest of the world can do anyway.