Culture and Corruption

‘Culture of corruption’ is a phrase bandied about far too often and easily by people who have never paused to consider its implications. Even here in Vanuatu, public discourse seldom gets beyond a troubling but tiresome litany of incidents. Passports for sale, illegal or unethical deals between cronies and political cadres, rumours of illicit cash… events pile up until our political dialogue resembles the inventory of a moral trash heap more than anything else.

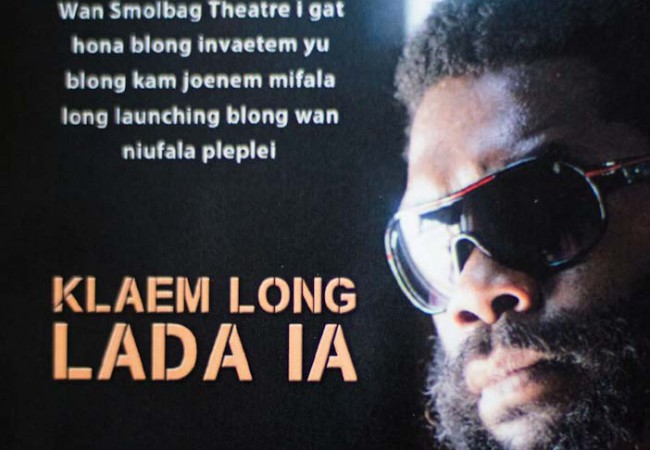

Wan Smolbag Theatre’s new play, Klaem Long Lada Ia (‘Climb that ladder’) gives shape and substance to Vanuatu’s painful descent from its idealistic beginnings and the inexorable spread of damage caused by venality, expediency and spiraling criminality. One bad deed, it seems, always deserves another, and another.

As with all her work, Jo Dorras’ script is rich and textured, her command of Bislama masterful, and only made better by contributions from the actors in the rehearsal process. The result is dialog that veers from scandalous, irreverent hilarity to shockingly raw outbursts as the play descends from satire to tragedy to near-despair.

The story tracks the ever-widening, ever-intensifying effects of corruption on multiple families. The plot keys off the actions of Arthur, a ‘bigman’ who brokers favours and funding for his political connections, allowing him to climb the ladder of success. But actions have consequences far beyond anyone’s imagining. Arthur’s pursuit of cash to pay off voters in the election campaign puts him in cahoots with serious operators, criminals from overseas who don’t hesitate to use intimidation, violence and even murder to extort an apparently endless list of ‘favours’ from the government.

Arthur is trapped in the middle of an escalating, expanding tragedy whose effects tear apart the lives of those around him. His constant willingness to indulge in expediency to profit himself and his family leads him ultimately to a bitter cynicism that seems on course to leave him, clothed as he is in the trappings of riches and power, a hollow man, a moral bankrupt.

Challenged by his shrewish wife about his willingness to ignore his own scruples in pursuit of success, he cuts her mid-sentence, reminding her that if it weren’t him, someone else would be accumulating these undeserved riches. ‘That’s the system we live in,’ he barks.

Arthur’s criminally short-sighted venality causes anguish throughout the tightly-woven, family-based community. Shorting his workers’ wages results in chronic need, driving mothers to beg, daughters to trade on their looks and men to sink into cynicism and the nihilism of drunkenness and abuse.

Arthur’s repulsive folly stands at the centre of this tragedy, but the play exposes truths seldom considered even by those who decry corruption the loudest. The story maps a rising spiral of physical and moral damage and with shocking suddenness stops, leaving us on the brink of even deeper despair, certain that things can only get worse. Only then, it asks: What will you do? Bound as we are, together in this cycle of damage, what possible choices can lead us out again?

This is, of course, the central question in Vanuatu society and politics today. How can we, so tightly bound together in this tiny corner of the world, find our way out? If, as Arthur suggests, the victory always goes to those who dive deepest in cronyism and corruption, what then must we do? Bowing out isn’t an option, he proclaims; that just opens the door for someone else to take your place at the trough.

The story is, quite literally, a knife in the guts. The characters may be nuanced and comically, tragically human –there are no angels here– but a chorus speaking directly to the audience, combined with graphic physical violence, ensures that the message is pounded home. Arthur’s world, our world, is not a happy place.

Since its inception 1989, Wan Smolbag has been one of the most fearless advocates for social issues, first in Vanuatu through its theatrical productions and workshops, and more recently throughout the Pacific with their television series Love Patrol. Founders Peter Walker and Jo Dorras, with the considerable support of dozens of superbly talented actors, technicians and designers, have created a small miracle, a gem in the Pacific. Using drama as their tool, they have crafted challenging, subtle messages that confront their audiences with the stark truth of the world they live in. In the midst of a conservative, often reticent culture, they’ve found a way for us to speak frankly about our problems.

Having spent a great deal of my adult life working for and with civil society, I am sometimes prone to see its weaknesses more often than its strengths. Without the levers of law and money, it often works at a distinct disadvantage to both government and business. This in turn can lead NGOs to fall victim to people too foolishly idealistic to be taken seriously, or, equally bad, people too timorous and beholden to donors to say anything worth taking seriously.

Wan Smolbag has found a way to engage, to confront the powers that be –and indeed the society in which it operates– with a full, nuanced portrayal of the problems we face. In addition to promoting dialogue, however, it has taken concrete steps to improve the lot of the underprivileged through a vast number of projects and activities, including health and social services, learning programmes and sports activities. It fills a critical gap by providing and supplementing basic services that the government struggles to maintain.

With over 150 staff, the NGO’s now-sprawling acreage is a haven for youth and adults alike, a space where, no matter how difficult the realities of day to day living, people can find safety, support and encouragement to look beyond present conditions and begin to frame a vision for the future that always looks upward.

Full disclosure: I have worked on a voluntary basis for Wan Smolbag on and off for years. But I don’t support them because I work with them; I work with them because I support what they do. I’ve seen the positive effects on a generation of Ni Vanuatu, and I believe that the next generation deserves at least as much a chance as the last.

Wan Smolbag’s model for engagement with society and politics, and for enacting positive change, is one that should be emulated, not only in the Pacific, but in all societies.