Beyond the Rainbow Warrior – the French Pacific catastrophe

France detonated 193 of a total of 210 nuclear tests in the South Pacific, at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls, before halting them in 1996 in the face of Pacific-wide protests. On 10 July 1985, French secret agents bombed the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour, killing photographer Fernando Pereira, in a futile bid to stop a protest flotilla going to Moruroa. A ni-Vanuatu citizen, Charles Rara, was on board. New Zealand journalist David Robie was on board the Rainbow Warrior for more than 10 weeks of its last voyage. His book Eyes of Fire tells the story and here he reflects about the Rainbow Warrior’s lasting legacy in the Pacific.

New Zealand wasn’t the only target of French special ops three decades ago. Nor was the Rainbow Warrior.

The attack on the Greenpeace environmental flagship 30 years ago was part of a Pacific-wide strategy to crush pro-independence movements in both New Caledonia and French Polynesia during the 1980s.

And Operation Satanique, as the Rainbow Warrior sabotage plan was aptly named, got the green light because of the political rivalry between then socialist President Francois Mitterrand and right-wing Prime Minister Jacques Chirac that pushed them into point-scoring against each other.

Although misleading and laughable as early New Zealand press reports were about who was responsible for the bombing on 10 July 1985 in Auckland Harbour – focusing on mercenaries, or the French Foreign Legion based in New Caledonia and so on – there was certainly a connection with the neocolonial mind-set of the time.

New Caledonia then had the largest military garrison in the Pacific, about 6000 French Pacific Regiment and other troops, larger than the New Zealand armed forces with about one soldier or paramilitary officer for every 24 citizens in the territory – the nearest Pacific neighbour to Auckland.

New Caledonia … highly militarised with French troops in the mid-1980s.

PHOTO: David Robie

A small Pacific fleet included the nuclear submarine Rubis, reputed to have picked up one unit of the French secret service agents involved in Operation Satanic off the yacht Ouvea and scuttled her in the Coral Sea and then spirited them to safety in Tahiti.

A long line of human rights violations and oppressive acts were carried out against Kanak activists seeking independence starting with a political stand-off in 1984, a year before the Rainbow Warrior bombing.

Parties favouring independence came together that year under an umbrella known as the Front de Libération Nationale Kanake et Socialiste (FLNKS) and began agitating for independence from France with a series of blockades and political demonstrations over the next four years.

The bombed Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour … not the only target of the French military. PHOTO: John Miller/Eyes of Fire

Melanesian activism

The struggle echoed the current Melanesian activism in West Papua today seeking political justice and independence from Indonesian colonial rule.

The Greenpeace tragedy was one of several happening in the Pacific at the time, and this was really overshadowed by the Rongelap evacuation when the Rainbow Warrior crew ferried some 320 islanders, plagued by ill-health from the US atmospheric mega nuclear tests in the 1950s, from their home in the Marshall Islands to a new islet, Mejato, on Kwajalein Atoll.

Rainbow Warrior crew helping Rongelap islanders board the ship for one of four voyages relocating them to Mejato islet in May 1985. PHOTO: David Robie/Eyes of Fire

Over the next few years, after the start of the Kanak uprising, New Caledonia suffered a series of bloody incidents because of hardline French neocolonial policies:

- The Hiènghene massacre on 5 December 1984 when 10 unarmed Kanak political advocates were ambushed by heavily armed mixed-race French settlers on their way home to their village after a political meeting. (Charismatic Kanak independence leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou lost two brothers in that ambush when almost all the menfolk of the village of Tiendanite were gunned down in one deadly night.)

- The assassination of Kanak independence leader Eloï Machoro and his deputy, Marcel Nonaro, by French special forces snipers at dawn on 12 January 1985 during a siege of farmhouse at Dogny, near la Foa.

- The infamous cave siege of Ouvea when French forces used a “news media” helicopter as a ruse to attack 19 young militant Kanaks holding gendarmes hostage, killing most of them and allegedly torturing wounded captives to death. The 11th Shock Unit carried out this attack – the same unit (known then as the Service Action squad) to carry out Operation Satanic against the Rainbow Warrior.

- The human rights violations involved in this attack were exposed in the 2011 docudrama Rebellion (originally L’ordre et la morale) by director Mathieu Kassovitz, based on a book by a hostage negotiator who believed he could have achieved a peaceful resolution.

[http://www.pjreview.info/sites/default/files/articles/pdfs/PJR18%282%29_Reviews_Rebellion%20pp212-216.pdf ] - France had its problems in Vanuatu too. Founding Prime Minister Father Walter Lini’s government expelled ambassador Henri Crepin-Leblond shortly before the election on 30 November 1987, accusing Paris of funding the opposition Union of Moderate Parties – a claim denied by the French.

French CRS special police confronting Kanak activists demanding independence in New Caledonia. PHOTO: David Robie

Social scars

The social scars from these events affected France’s standing in the Pacific for many years. While relations have dramatically improved since then, it still rankles with both many New Zealanders and Greenpeace that Paris has never given a full state apology.

Interviewed on Democracy Now! recently, Rainbow Warrior skipper Pete Willcox, who is returning to New Zealand to captain the ship for a tuna fishing campaign, criticised the failure of France to apologise for being “caught red-handed” in state terrorism.

However, the American also delivered a strong warning about climate change – the main contemporary environmental issue.

Explaining his more than three decades of campaigning, Willcox said: “We know what climate change is doing. We’re the richest country in the world. We can support, if you will, a drought.

“Countries like in East Africa and other places of the world, Bangladesh, where it’s going to displace millions of people, can’t deal with it. And it’s coming.

“And it’s only coming because we’re not willing to change the way we produce energy, we make energy. We have the technology. We don’t have the will. And that’s just ridiculous.”

In January 1987, a year after my book Eyes of Fire was first published – four months before the first Fiji military coup, I was arrested at gunpoint by French troops near the New Caledonian village of Canala.

Tailed by agents

The arrest followed a week of me being tailed by secret agents in Noumea. When I was handed over by the military to local gendarmes for interrogation, accusations of my being a “spy” and questions over my book on the Rainbow Warrior bombing were made in the same breath.

But after about four hours of questioning I was released.

David Robie presenting an earlier edition of Eyes of Fire to former Vanuatu Prime Minister Ham Lini in 2006. PHOTO: Pacific Media Centre

This drama over my reporting of the militarisation of East Coast villages in an attempt by French authorities to harass and suppress supporters of Kanak independence was a reflection of the paranoia at the time.

Then it seemed highly unlikely that in less than two decades nuclear testing would be finally abandoned in the South Pacific, and Tahiti’s leading nuclear-free and pro-independence politician, Oscar Manutahi Temaru, would emerge as French Polynesia’s new president four times and usher in a refreshing “new order” with a commitment to pan-Pacific relations.

Although Tahitian independence is nominally off the agenda for the moment, far-reaching changes in the region are inevitable.

President Baldwin Lonsdale remarked about the Rainbow Warrior bombing in a welcome for the ship’s namesake, Rainbow Warrior III, in Port Vila recently on her post-cyclone humanitarian mission.

He recalled how the Vanuatu government representative, the late Charles Rara, sent by founding Prime Minister Walter Lini on board the Rainbow Warrior to New Zealand, had been ashore on the night of the bombing. Rara was at the home of President Lonsdale at St John’s Theological College in Auckland, where he was studying.

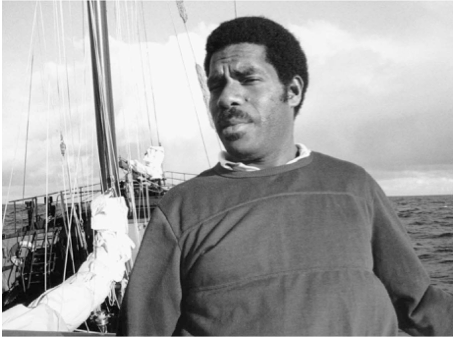

The late Charles Rara, Vanuatu’s “diplomatic” representative on board the Rainbow Warrior bound for Auckland in 1985. PHOTO: David Robie/Eyes of Fire

“When Charles got back to the ship that night, he found the Rainbow Warrior had been bombed, it had been destroyed,” President Lonsdale said.

“I think the main intention of the French [military] who carried out the bombing was because the Greenpeace movement was trying to bring about peace and justice among island nations.”

‘Living reef’

After being awarded $8 million in compensation from France by the International Arbitration Tribunal, Greenpeace finally towed the Rainbow Warrior to Matauri Bay and scuttled her off Motutapere, in the Cavalli Islands, on 12 December 1987 to create a “living reef”.

An earlier compensation deal for New Zealand mediated in 1986 by United Nations Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar awarded the Government $13 million (US$7 million) – the money was used for an anti-nuclear projects fund and the Pacific Development and Conservation Trust.

The agreement was supposed to include an apology by France and deportation of jailed secret agents Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieur after they had served less than a year of their 10-year sentences for manslaughter and wilful damage of the bombed ship (downgraded from charges of murder, arson and conspiracy).

They were transferred from New Zealand to Hao Atoll in French Polynesia to serve three years in exile at a “Club Med” style nuclear and military base.

But the bombing scandal didn’t end there. The same day as the scuttling of the Rainbow Warrior in 1987, the French government told New Zealand that Major Mafart had a “serious stomach complaint”. The French authorities repatriated him back to France in defiance of the terms of the United Nations agreement and protests from the David Lange government.

It was later claimed by a Tahitian newspaper, Les Nouvelles, that Mafart was smuggled out of Tahiti on a false passport hours before New Zealand was even told of the “illness”. Mafart reportedly assumed the identity of a carpenter, Serge Quillan.

Captain Prieur was also repatriated back to France in May 1988 because she was pregnant. France ignored the protests by New Zealand and the secret agent pair were honoured, decorated and promoted in their homeland.

Supreme irony

A supreme irony that such an act of state terrorism should be rewarded in this age of a so-called “war on terrorism”.

In 2005, their lawyer, Gerard Currie, tried to block footage of their guilty pleas in court – shown on closed circuit to journalists at the time but not previously seen publicly – from being broadcast by the Television New Zealand current affairs programme Sunday.

Losing the High Court ruling in May 2005, the two former agents appealed against the footage being broadcast. They failed and the footage was finally broadcast by Television New Zealand on 7 August 2006 – almost two decades later.

French secret agent Alain Mafart pleads guilty to reduced charges of manslaughter and wilful damage in November 1985 (courtroom CCTV footage). PHOTO: TVNZ

They had lost any spurious claim to privacy over the act of terrorism by publishing their own memoirs – Agent Secrète (Prieur, 1995) and Carnets Secrets (Mafart, 1999).

Mafart recalled in his book how the international media were dumbfounded that the expected huge High Court trial had “evaporated before their eyes”, describing his courtroom experience:

I had an impression of being a mutineer from the Bounty … but in this case the gallows would not be erected in the village square. Three courteous phrases were exchanged between [the judge] and our lawyers, the charges were read to us and the court asked us whether we pleaded guilty or not guilty. Our replies were clear: ‘Guilty!’ With that one word the trial was at an end.

Ironically, Mafart much later became a wildlife photographer, under the moniker Alain Mafart-Renodier, and filed his pictures through the Paris-based agency Bios with a New York office. Greenpeace US engaged an advertising agency to produce the 2015 environmental calendar illustrated with wildlife images.

As Greenpeace chronicler and photojournalist Pierre Gleizes describes it: “Incredibly bad luck, out of millions, the agency bought one of Alain Mafart’s pictures to illustrate a Greenpeace calendar. Fortunately, someone saw that before it got distributed. So Mafart got his fee but 40,000 calendars were destroyed.”

French nuclear swansong

France finally agreed to sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty after a final swansong package of eight planned nuclear tests in 1996 to provide data for simulation computer software.

But such was the strength of international hostility and protests and riots in Pape’ete that Paris ended the programme prematurely after just six tests.

France officially ratified the treaty on 10 September 1996.

When Tahitians elected Oscar Temaru as their territorial president in 2004, he had already established the first nuclear-free municipality in the Pacific Islands as mayor of the Pape’ete airport suburb of Faa’a.

Having ousted the conservative incumbent for the previous two decades, Gaston Flosse – the man who gave Mafart and Prieur a hero’s welcome to Tahiti, Temaru lost office just four months later.

He was reinstated to power in early 2005 after a byelection confirmed his overwhelming support. But since then Temaru has won and lost office twice more, most recently in 2013, and Flosse is fighting ongoing corruption charges.

Since the Temaru coalition first came to power, demands have increased for a full commission of inquiry to investigate new evidence of radiation exposure in the atmospheric nuclear tests in the Gambiers between 1966 and 1974.

‘Contempt’ for Polynesia

Altogether France detonated 193 of a total of 210 nuclear tests in the South Pacific, 46 of them dumping more than nine megatons of explosive energy in the atmosphere – 42 over Moruroa and four over Fangataufa atolls.

The Green Party leader in Tahiti, Jacky Bryant, accused the French Defence Ministry of having “contempt” for the people of Polynesia.

Replying to ministry denials in May 2005 claiming stringent safety and health precautions, he said: “It’s necessary to stop saying that the Tahitians don’t understand anything about these kinds of questions – they must stop this kind of behaviour from another epoch.”

Bryant compared the French ministry’s reaction with the secretive and arrogant approach of China and Russia.

However, Britain and the United States had reluctantly “recognised the consequences of nuclear tests on the populations” in Australia, Christmas Island, the Marshall Islands and Rongelap.

In 2009, the French National Assembly finally passed nuclear care and compensation legislation, known as the Morin law after Defence Minister Hervé Morin who initiated it. It has been consistently criticised as far too restrictive and of little real benefit to Polynesians.

In 2013, declassified French defence documents exposed that the nuclear tests were “far more toxic” than had been previously acknowledged. Le Parisien reported that the papers “lifted the lid on one of the biggest secrets of the French army”.

It said that the documents indicated that on 17 July 1974, a test had exposed the main island of Tahiti, and the nearby tourist resort isle of Bora Bora, to plutonium fallout 500 times the maximum level.

US radiation fallout

This had been echoed almost two decades earlier when The Washington Post reported that US analysts had admitted that radiation fallout from their nuclear tests of the 1950s was “limited”.

In fact, federal documents, according to The Post in the February 1994 article, had revealed that “the post-explosion cloud of radioactive materials spread hundreds of [kilometres] beyond the limited area earlier described in the vast range Pacific islands”.

Thousands of Marshall Islanders and “some US troops” had probably been exposed to radiation, the documents suggested.

“One of the biggest crimes here is that the US government seemed to clearly know the extent of the fallout coming, but made no attempt to protect people from it,” said Washington-based lawyer Jonathan Weisgall, author of Operation Crossroads, a book about the Marshall Islands nuclear tests.

The Rainbow Warrior bombing with the death of photographer Fernando Pereira was a callous tragedy. But the greater tragedy remains the horrendous legacy of the Pacific nuclear testing on the people of Rongelap and the Marshall Islands and French Polynesia.

More information about the Rainbow Warrior affair can be found here.