Island identity

The tradition of public dialogue extends beyond recorded history in Melanesia. Village meetings in which the entire community turns out to hear and be heard are perhaps their most enduring social and political institution. It’s hardly surprising, therefore, that the question of online anonymity is one to which the citizens of Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu appear to be responding with a resounding ‘no’.

During a recent panel discussion on social media, former MP Joshua Kalsakau stated the case against the use of ‘kiaman’ (lying) names, as pseudonyms are known in Vanuatu. The tradition, he said, of everyone in a village coming together in the nakamal, or meeting house, to discuss issues openly and honestly, to uphold or oppose, and ultimately to arrive at consensus, lies at the very root of Vanuatu society. Words may be heated, he continued, but opposition and disputation are part of our culture too.

A consultation conducted by Forum Solomon Islands International, a registered NGO that grew out of the most popular Facebook group in the country, asked for input on the proposition that ‘all members who exist with an alias name provide their real identity against there [sic] FB status.’ Citing the need to build ‘human relationships’, the group’s administrators characterised the measure as evidence of their maturity and responsibility. In the 100 comments that ensued, support was nearly unanimous.

In Papua New Guinea, a draft cybercrime policy recently submitted to cabinet by the National ICT Authority, or NICTA, recommends compulsory registration of all new SIM cards in mobile phones, and the criminalisation of anonymity in cases of online abuse. Charles Punaha, NICTA’s CEO, told The National newspaper that ‘we are going to make it an offence for people to use pen-names, not using their real names and abusing the social media and making defamatory statement[s].’

These new policy proposals have so far passed largely without comment in PNG social media. Sharp Talk, a locus of online political and social commentary, left the issue undiscussed. PNG ICT Community, a technology-oriented Facebook group, devoted a single thread to compulsory SIM registration, which a majority saw as a necessary curb to anti-social and sometimes criminal abuse of mobile phones.

Of the 42 comments the thread generated, only one suggested that ‘we need researched facts, analysis and evidence to tell us that there is a threat for cybercrime and SIM card identity theft and abuse-reported stats must be produced to indicate that [it’s] a problem….’

No compelling evidence has yet emerged that requiring the use of ‘real’ online identities achieves the goal of reducing the incidence of libel, rumour-mongering or other forms of abuse. In 2012, the South Korean constitutional court struck down a law requiring registration to popular online services, citing not only the ineffectiveness of the measure, but its chilling effect on free speech.

But evidence, or lack thereof, doesn’t seem to come into it when online identity is discussed in Melanesia. Reflexive rejection of the concept seems to be rooted in a simple fact of island life – everyone knows everyone else. Mistrust of strangers goes beyond mere suspicion; there is a strong and pervasive feeling that those who are not of a place have no right to speak about its issues, especially to criticise.

A case in point: An unfavourable travel review from the Lonely Planet website was recently copied into Vanuatu’s 13,000-strong Facebook group Yumi Toktok Stret. The responses that followed were rife with vilification for the unfortunate tourist. Swearing and threats of violence were posted without objection either from the group’s administrators or other commenters. Among the politer suggestions was one that the tourist ‘go get lost somewhere in outer space with ET.’

Full disclosure: I publish the majority of my writing and photography under a pseudonym, and have done so since 1995. It provides a paper wall between my professional life and my creative endeavours, as well as allowing me a bit of personal space: Those who know me only professionally won’t be dragging me into personal conversations.

But those who have felt the sharp end of public opinion, or whose pronouncements have brought political pressure to bear, are equally concerned about the cost of requiring ‘real’ identities online. Award-winning PNG blogger Martyn Namorong recently made his blog invitation-only, citing political and legal pressures.

One long-time observer of social media in Solomon Islands states, ‘the communal culture is manipulated by the new elites created during and after independence; the big man concept is manipulated and abused and I think many realise it, and the[y] need to be able to speak out without fear of recrimination – and that means anonymously.’

One long-time observer of social media in Solomon Islands states, ‘the communal culture is manipulated by the new elites created during and after independence; the big man concept is manipulated and abused and I think many realise it, and the[y] need to be able to speak out without fear of recrimination – and that means anonymously.’

When we argue that there is no anonymity in island culture, we ignore as well that the art of gossip is a master class in Melanesia. Rumours affect everyone, often negatively.

Although the majority of people posting online today disagree with the concept of anonymity, their reaction might well change when faced with its necessity. It’s one thing for adult males in Melanesian societies to advocate standing up proudly in defence of their opinion. It’s another thing entirely for the majority of women and youth to do so. An ad hoc scan of posts and comments on the Yumi Toktok Stret Facebook group shows a dearth of commentary from women, especially young women, in spite of the fact that approximately half of all Vanuatu Facebook users identify as female.

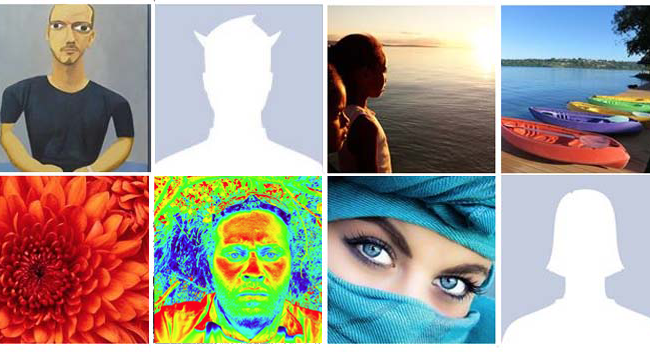

It is noteworthy –and likely not accidental– that young women and men seem to be the most inventive when it comes to registering their name with the service. A common local affectation, perhaps Vanuatu’s answer to the hacker community’s so-called ‘l33t spe4k’, is to remove the vowels from one’s Facebook name. It’s a useful shorthand that allows those who know you already to decipher the name, but keeps strangers in the dark.

Identity, as it is widely understood in Melanesia, is changing.

More and more public dialogue is being conducted online, rather than face-to-face. And memory is not as fleeting or forgiving as it once was. A common feature of village and family meetings is the ferocity with which some of them begin. To an outsider, it can appear that the interlocutors are about to come to blows. But by the end, even the most fiery exchanges are forgotten, hands are shaken all round, and peace is restored.

Online, everyone’s rashest comments and actions are stored for posterity. It is sometimes useful or necessary to make a fresh start, to separate oneself from the past. Doing so in Melanesia requires a painful schism with tradition.

[The original version of this post erroneously identified Forum Solomon Islands as the name of a registered civil society organisation. The actual name is Forum Solomon Islands International. The text has been corrected to reflect this fact.]