Fighting a running tide

Last week, I quietly enjoyed a historic moment in my career in technology. From my home in Port Vila, I played a game of Counterstrike on a server in Sydney. That may not sound like much to you, but for people here in Vanuatu, it’s been a long time coming.

After nearly ten years of wrangling, lobbying, cajoling, and no small amount of bickering, Vanuatu’s ISPs have finally begun to roll out services connecting their customers to the new fibre-optic cable. The improvement is startling. Until the cable was brought into service, our entire nation had been stuck using satellite connectivity.

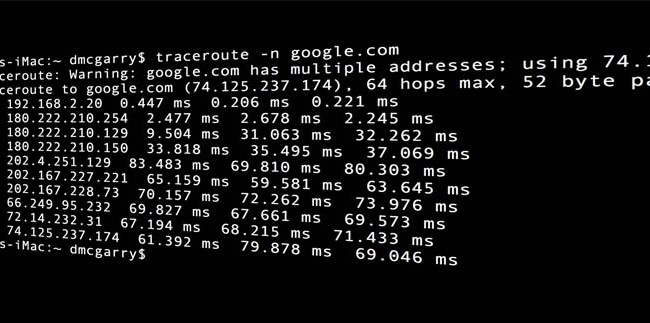

Having any internet at all is a blessing, but satellite internet is a decidedly mixed one. The satellite circles the Earth at a distance of nearly 36,000 kilometres. It orbits at exactly the right speed to make it appear motionless from the surface of our spinning globe. But at such a distance, it takes about a quarter of a second for a radio signal to reach it. Add another quarter of a second for the satellite to relay the signal back to earth, and then double that again for the time it takes to receive a reply.

Thanks to a little bit of radio engineering magic, the real delay is somewhat less than a second, but that’s small comfort to anyone trying to do anything in real time. A Skype conversation, for example, can be an awkward, stumbling experience, as the delay between the connected parties often causes people inadvertently to talk over one another. Watching a video is a painful experience, too, because every time the data stream loses its place (altogether too often, what with our congested lines and shaky infrastructure), it takes a long time to re-establish the connection. Typically, we spent more time buffering than watching.

Happily, all that is in the past. At least, it is for those privileged few in the capital who have the means to pay for the service.

Back in 2010, I wrote:

Uptake on Internet is still limited to a tiny minority. The pool of Internet users has risen substantially… but as a percentage of population, the numbers are still so small that, in a recent national telecoms survey, the researchers declined even to ask about Internet. The data set was too small to be relevant.

Prices today have effectively risen, megabit for megabit, relative to developed markets. Oh, they’ve dropped from the stratospheric levels they used to inhabit (US $1000/month for 128 Kbps and a 100 MB download limit). But you still pay over US $500/month for a single megabit which, occasionally, actually delivers a megabit of bandwidth. When it works.

Most depressing of all, the total amount of bandwidth available for the entire country is only slightly more than the average bandwidth capacity of a single household in Seoul, Korea.

Notwithstanding our steady progress as a nation – among best in the Pacific islands – much of what I wrote four years ago is still true.

We did, ultimately, include internet use in a subsequent survey. The 2011 Net Effects survey showed that a mere 12% of over 1000 respondents from around the country had actually used the internet at any time in their life. Prices have improved remarkably compared to what they used to be, and the cable has had a wonderfully salutary effect on the quality of the service. But the price of entry is still relatively high. Even the most meager options for an always-on internet connection still hover between 3000-4000 vatu. That’s somewhat more than 10% of the monthly minimum wage here.

At least we have capacity, if we ever find a way to pay for it. In theory, at least, the cable has about 20 Gigabits per second in available bandwidth. The actual amount of bandwidth commissioned and in use at this moment has not been announced, but it’s a very small fraction of the total.

Getting this bandwidth out to the islands is going to be a monumental task. Indeed, just getting a cable at all was a more painful experience than it ever should have been. We should by rights be celebrating the second anniversary of the cable’s roll-out, not its inauguration. But as with so many relatively large-scale undertakings in this tiny place (the cost represents about 4% of GDP), the stakes were such that virtually every aspect of the scheme became enmeshed within the byzantine maze of local interests. The longer-term viability of the undertaking is looking better now, but it’s still far from certain.

That said, the government of Vanuatu has been perfectly clear in its determination that the nation as a whole should benefit. Without its intervention, it’s doubtful the Vanuatu National Provident Fund would have become the project’s largest investor.

The government and the telecommunications regulator are now intent on determining how to achieve the policy goal of access to broadband internet for 98% of the country’s population by 2018. It’s a formidable challenge. The Universal Access Policy defines broadband as 21 megabits download speed, and 12 megabits upload. By global standards, that’s a pretty middle of the road figure. But how will it look in four years time?

And that’s assuming we ever get there. ISPs are not at all happy with the policy’s ‘play or pay’ approach, which requires that all ISPs either demonstrate how they’re going to contribute to this goal, or face a levy of up to 4% of profits. They claim that there is far too much ambiguity in the policy as it stands, and that they are being forced to make the running with little guidance or assistance from the policy makers themselves.

Some have said that the goal itself is not attainable. The original expectation was that broadband should consist of 42 megabits per second down and 21 megabits up. But even with the number cut in half, they say, the prospects for success are vanishingly small.

They’re not entirely wrong. Even counting the government’s own national backbone network, there is simply no way to carry more than the slightest fraction of the cable’s capacity to islands other than Efate. And if our experience with the cable is any guide, building out domestic capacity will require years of potentially fractious, disputatious wrangling. Plans to increase national backbone capacity by two orders of magnitude would have to be in hand now, today, if we’re to have any chance whatsoever.

It would be presumptuous to assume that Ni Vanuatu would be willing (or able) to spend more than one or two thousand vatu per month on internet. Even at that level, we would be asking them to double their average monthly spend on communications. And that’s assuming that villagers would have access to sufficient electrification to keep a smart phone or a tablet charged.

Even with the submarine cable’s significantly reduced internet prices, ISPs cannot reasonably be expected to drop their prices much further and still remain profitable.

Something (or someone) has got to give. At some point, we’re going to have to face up to the fact that a purely private-sector driven internet can never match the rate of progress of other developing countries, let alone catch up to them.

We do have options: If the submarine cable company were reorganised as an industry consortium, it would be able to reduce international transit prices to the barest minimum, and guarantee fair dealing with all ISPs. Connecting the cable to a second source (PNG, for example) would allow us to sell transit to international backbone providers. This, according to one veteran backbone operator, could reduce transit costs to as little as a tenth of what they are today.

But that still doesn’t get internet service into even our more accessible, populous islands. And given the sizeable and rising levels of debt repayment the government is currently facing, it’s not realistic to expect the state to bear the burden alone. Ultimately, regional and global donors will have to decide just how important it is to them to see Vanuatu’s people keep abreast of a rising internet tide that, right now, is driving us backwards, no matter how we sail the ship.