Press Freedom involves being called ‘stupid’

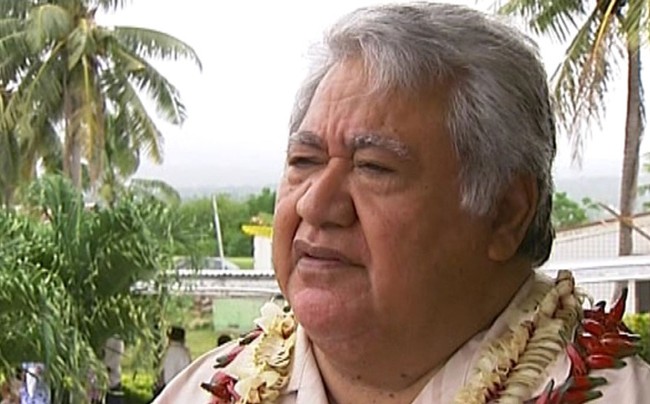

Samoa’s Prime Minister, Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegoai called a report from the Samoan Observer “stupid” and accused the newspaper that they “don’t understand what they are doing.” The Prime Minister and the newspaper have clashed in the last few months over critical stories published.

The latest story was a report that an independent audit has found the Samoa Rugby Union, whose chairman is the prime minister, in deficit of nearly $1.5 million tala (NZ$800,000). The prime minister acknowledged in remarks to the media that the Samoa Rugby Union has financial problems but was obviously annoyed with the story.

The Samoa Observer, a daily, is Samoa’s biggest newspaper. It has accused the prime minister of violating media freedom, and wanting “to control the media.”

In my media life of almost twenty-five years I have been involved in fighting for media freedom not only in my home country of Tonga but also in the Pacific region, including the Pacific media in New Zealand.

I have been called all kinds of names by those that have been under the scrutiny of my media news outlets; and my newspaper, the flagship of our operation, has been called “scurrilous”, “controversial”, “anti-establishment”, “anti-government”, “anti-royal”, “anti-cultural”, “anti-Tongan”, “trash-sheet”, and other names not suitable for mention here. I have ceased however, to count the number of times our newspaper (and myself) has been called “stupid”.

Most of the accusations or “put-downs” came from government leaders who were the main actors in news stories ran by the newspaper. During the eighties and early nineties, Tongan authorities were not accustomed to being criticised or at least being exposed negatively in news stories.

There were some significant moves on the part of government to shut us down, and some of those actions were successful. We were banned for several months from distribution in Tonga, and I was personally banned from entering Tonga without a written permit from Tongan Immigration. The worse came in 1996 when I was jailed together with my deputy editor and an MP for contempt of parliament. We were later released from jail after 26 days, thanks to a judgment by the Tongan Supreme Court, on our habeas corpus application.

A Papua New Guinea editor, Frank Senge Kolma wrote about us: “In reality they were jailed for telling the people of Tonga about a matter which the people had a right to know.”

Government attitude in the 1990’s toward media freedom was one where “you only have the right to know what we allow you to know; if you insist on knowing more or report beyond that, you are a rebel, seditious, and culturally insensitive.”

But those days of such incredibly unnecessary treatment seem to be behind us.

The mid-2000 have been more kind to us despite new attempts at times to legislate against media freedom, and push for self-regulation through a proposed government controlled media council.

My view is that the government of Tonga has become more matured in their understanding of what media freedom is, as well as a general culture shift in Tongan society from closed communication to an open one.

But what is more concerning nowadays is a major shift in the concept of media freedom, and it is not coming from government but is perpetuated by those who have been advocating for freedom of speech and freedom of the press in earlier years.

It is a new twist on an old adage, that we are free “to speak truth to power”, but it depends who holds the power. This is taken to mean that media is the watchdog of organised government, but does not have the freedom to question those in the opposition. There is a sense here of “partisanship freedom”, a “right to freedom by belonging to the right group.” We have a mindset that our group’s freedom may be protected and fought for, but not the freedom of those who do not belong to us, and who may hold contradictory views.

In other words, “you have the freedom to speak against government” but you do not have the freedom “to speak against us (the opposition).” Its like saying, “the right to freedom of speech belongs to us, but not to you.” “You are free to speak if you are agreeable with us, but if you speak anything to the contrary, you are not free to speak.”

This twisted notion of media freedom is what is being flaunted unfortunately in Tonga, and most of the South Pacific island states. Government is not necessarily the one in opposition to media freedom but the media itself who are in dissension with each other. Governments know this, and in a number of countries have used this leverage against offending media. The saying that “a divided house cannot stand” has characterised a divided media field that is becoming more and more uneven.

The dissension and subsequent conflict among media is primarily based on this very shallow and misguided concept of media freedom. If I want to have media freedom, then I must let the others have their media freedom also, the freedom to speak, even if they do not agree with me.

For those of us in media who have been the bastion of media freedom, it is equally important for us to be vigorous in advocating for the freedom of speech of others, especially those whose views or opinions are different or in opposition to ours. This, in my view, is the highest level of commitment to media freedom, and more so in societies worldwide that are pluralistic. Media freedom is a legal fact in most Pacific island constitutions, but it is the practical application of it to our cultures that makes the difference. This is a key issue in moving any island society forward in democratisation.